Introduction

What if I were to tell you that I was going to discuss the second most common foot injury in athletes, that is missed or misdiagnosed in 1 in every 5 cases? Is that something you might be interested in?

Well that is what happening… Lisfranc joint injuries are a challenging presentation in an athletic population. As stated above, they are relatively common and regularly misdiagnosed. However, unfortunately they have the potential to develop into a CAREER-ENDING injury! Undoubtedly, this makes prompt and accurate diagnosis and evidence based management exceptionally important.

What Is A Lisfranc Joint Injury?

The term “Lisfranc joint” refers to the tarso-metatarsal (TMT) joints. The “Lisfranc ligament” connects the base of the medial cuneiform to the base of the 2nd MT. Lisfranc joint injuries are the second most common foot injury in athlete (Brukner and Khan, 2008). Lisfranc joint injuries include a spectrum of injury from a simple sprain of the Lisfranc ligament through to complex fracture dislocation injuries. This injury spectrum is discussed below in the Classification.

Mechanism of Lisfranc Joint Injury

The mechanism of injury leading to a Lisfranc injury can be divided into: high and low velocity injuries.

- High Velocity: Most commonly, the foot gets forced into hyper-plantarflexion, with an additional valgus or varus component. The high energy force frequently disrupts the osteoligamentous restraints of the Lisfranc joint. This will dislocate the Lisfranc joint and result in gross instability and often neurovascular damage. These injuries have a high risk for compartment syndrome because of soft-tissue swelling and disruption of the dorsalis pedis artery. Think falling backwards of a horse with a foot in a stirrup

- Low Velocity: These typically follow one of two mechanisms. The first is forced hyper-plantarflexion of the midfoot. The seocond is an axial load through the foot, whilst the foot is plantarflexed and the MTP joints are dorsiflexed (Shapiro et al., 1994). Think someone landing on a foot in the sprint start position.

Diagnosis Of Lisfranc Joint Injury

The following are representative of the typical examination findings for a Lisfranc joint injury (Lattermann et al., 2007; Mulieri et al., 2010):

Subjective Examination:

- The clinician should maintain a high clinical suspicion of Lisfranc injury. This is particularly true in presentations of ankle and/or foot sprains.

- The athlete may report a mechanism of injury similar to that above. However, in the subtle Lisfranc injuries frequently the athlete will not report any significant mechanism of injury.

- Pain: is frequently felt locally over the Lisfranc joint injury, and may extend down the meta-tarsals.

Objective Examination:

- Observation: there may be focal swelling. A soft delayed sign is a ecchymosis on the plantar aspect of the foot.

- Palpation: you should palpate the navicular, medial, and middle cuneiforms and the bases of the first through fifth metatarsals. Lisfranc ligament tenderness will be palpated for in the space between first and second metatarsals.

- Passive Accessory Motion: The stability of the “Lisfranc row” i.e. the first to fifth TMT joints can be assessed by passive pronation and supination of the forefoot. Additionally the Lisfranc joint can be stressed via passive dorsiflexion and abduction of the forefoot. Pain with these movement should increase your clinical suspicion.

- NB: A full neurovascular examination is essential given the possibility of injury to these structures (disruption of the dorsalis pedis artery).

Imaging for Lisfranc Joint Injury

X-Ray: anteroposterior (A-P), a 30-degree oblique, and a lateral view of the foot are required. Weight-bearing views, if tolerated, are strongly recommended and will help accentuate any deformities, especially for subtle Lisfranc joint diastasis. There are a few things which can be taken from these views (Mulieri et al., 2010). This includes:

- Fleck sign: an avulsion fracture of the Lisfranc ligament

- Diastasis distance between the 1st and 2nd meta-tarsal

- Medial arch height (medial cuneiform vs. base of 5th)

- Any other fractures.

Computed Tomography: for subtle Lisfranc injuries CT scanning may show small, bony avulsions that can be helpful in the diagnosis. CT is essential for planning of surgical interventions in more complex Lisfranc injuries, including Lisfranc fracture dislocations.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): will help detect mild Lisfranc sprains with a partial disruption or significant edema visible in the Lisfranc ligament and the surrounding first TMT joint capsule. MRI diagnosis of complete or grade 2 Lisfranc ligament injury has been shown to be accurate and predictive of instability assessed intra-operatively (Raikin et al., 2009).

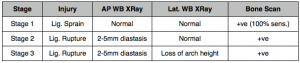

Bone Scan: This has been shown to be 100% sensitive for Stage 1 Lisfranc injuries as discussed below. This is importantas these injuries will not appear abnormal of x-ray. Bone scan can also be particularly useful for athletes with a delayed examination.

Classification of Lisfranc Joint Injury

Nunley and Vertullo (2002) classified Lisfranc injuries into a system based on clinical examination, bone scan results and weight-bearing radiographs. I feel this is clearly the most relevant classification for physiotherapists, as these are the patients that will turn up in our clinics. The weight bearing radiographs included a weight bearing (WB) AP to examine any diastasis between the 1st and 2nd metatarsals, and a WB lateral view to assess medial arch height.

Whilst this is a great classification system, particularly for physiotherapists, for assessing and classifying Lisfranc joint sprains it does not take into account the more complex of Lisfranc joint injuries. There is where Myerson et al. (1986) step in. They developed a classification system for complex fracture/dislocations of the Lisfranc joint:

- Type A: Total incongruity in any plane or direction.

- Type B: Partial incongruity/homolateral incomplete. This was divided further.

- Type B1: which affects the medial articulation alone

- Type B2: which affects the lateral articulation alone

- Type C: Divergent/total or partial displacement when the medial and lateral metatarsals are displaced in opposite directions and opposite planes. This was further divided.

- Type C1: Fewer than 4 metatarsals involved.

- Type C2: All 4 metatarsals involved.

For an image of this classification system which opens in a new window (so that it all makes sense) click here.

Conservative Management of Lisfranc Joint Injury

A stage 1 Lisfranc injury, i.e. < 2 mm diastasis between the base of the first and second metatarsals, is considered functionally stable. This means that these injuries can be treated non-operatively. Unfortunately, the recommendations range from immediate weight bearing in an orthotic with arch support to non–weight bearing in a cast for 6 weeks (Latterman et al., 2007). Management of 6 weeks in a non-weightbearing cast, followed by moulded orthotics delivered excellent results in athletes with Stage 1 Lisfranc ligament injuries (Nunley and Vertullo, 2002).

If using conservative management with a boot cast the literature recommends that a repeat X-ray be performed after 2 weeks (Latterman et al., 2007). This can be used to re-assess the diastasis and ensure no progression. If at this 2 week re-assessment the injury is stable and the athlete is clinically non-tender then progression into weight-bearing activities with orthotics may be commenced i.e. removal of boot cast (Latterman et al., 2007). Otherwise, the athlete should remain in the non-WB cast for 6 weeks, as described by Nunley and Vertullo (2002).

Surgical Management of Lisfranc Joint Injury

Any Lisfranc injury above a stage 2 i.e >2mm or greater diastasis or that involves a fracture requires a referral to an orthopaedic specialists. They will undertake appropriate management which can include closed reduction and internal fixation (CRIF), open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) and/or screw management of fracture sites.

Return to Play Outcomes

Nunley and Vertullo (2oo2) showed RTP rates in 15 athletes following either conservative or surgical management:

- Stage 1: Excellent outcome with conservative management and RTP between 11 and 18 weeks.

- Stage 2 (Either B1 or B2): Mostly excellent outcomes with ORIF or CRIF, with athletes RTP between 12 and 20 weeks. Poor outcomes were noted in some athletes who displayed diastasis (>2mm) on X-ray and were managed non-operatively.

- Complex Lisfranc Injuries: RTP time-frames is not well reported in significant injuries including significant fracture dislocations. However, it is safe to assume that these injuries are season ending, with likely RTP rates longer than Stage 2 injuries.

Take Home Messages

- You must maintain a high clinical suspicion for these injuries

- Early and accurate diagnosis is essential for Lisfranc joint injuries to ensure the quickest RTP

- In many cases these are not massive injuries with a significant mechanism

- Bone scan and WB X-Rays are the most useful diagnostic images for subtle Lisfranc injuries

- Differentiation between Stage 1 and Stage 2 injuries is essential to ensure the best outcome for the athlete

- Reported outcomes are excellent and RTP for lower grade injuries is 3 – 5 months.

What are your thoughts on the diagnosis and management of Lisfranc joint injuries? Let me know in the comments or catch me on Facebook or Twitter

If you require any sports physiotherapy products be sure check out PhysioSupplies (AUS) or MedEx Supply (Worldwide)

Photo Credit: Park Street Parrot, WikiCommons

References

Brukner, P. and Khan, K. Clinical Sports Medicine. Revised Second Edition. (2008). McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd.

Lattermann C, Goldstein JL, Wukich DK, Lee S, Bach BR. Practical Management of Lisfranc Injuries in Athletes. Clin J Sport Med 2007;17:311–315

Mulieri T, de Hann J, Vriesendorp P, Reynder P. The Treatment of Lisfranc Injuries: Review of Current Literature. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2010;36:206–16

Myerson MS, Fisher RT, Burgess AR, et al. Fracture dislocations of the tarsometatarsal joints: end results correlated with pathology and treatment. Foot Ankle. 1986;6:225–242.

Nunley J, Vertullo C. Classification, Investigation, and Management of Midfoot Sprains: Lisfranc injuries in the athlete. Am J Sports Med 2002;30(6):871–878.

Raikin SM, Elias I, Dheer S, Besser MP, Morrison WB, Zoga AC. Prediction of Midfoot Instability in the Subtle Lisfranc Injury: Comparison of Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Intraoperative Findings. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:892-9

Shapiro MS, Wascher DC, FInerman GA. Rupture of Lisfranc’s ligament in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:687–691.

Related Posts

Comments

Brilliant Article, really useful to reference if needed. Highlights the importance of aggressive early PRICE principles and how not putting a midfoot sprain injury in a boot straight away could cause significant damage until lisfranc is excluded!