INTRODUCTION

Patellar dislocation accounts for 2 – 3% of all knee injuries, however, is the second most common cause of knee haemarthrosis (Aglietti et al., 2001). Patellar dislocation is most commonly associated with sports injuries, and therefore, is encountered commonly by the sports physiotherapist. In recent times there has been controversy on the most appropriate forms of management following primary (or first time) patellar dislocation. This post discusses evidence based management of primary patellar dislocations.

SUBJECTIVE EXAMINATION

The athlete will often report:

- Genus of traumatic or non-traumatic dislocation

- Perception of ‘kneecap movement’

- Intense pain

- ‘Snapping’ sensation

- Past History of dislocation (on either limb) is prognostically important. This indicates a 6 fold increase in risk of re-dislocation (Jain et al., 2011)

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

On initial physical examination you will often find:

- Observation: Haemarthrosis present (patellar dislocation is the second most common cause of haemarthrosis)

- AROM: decreased ROM, secondary to pain and effusion

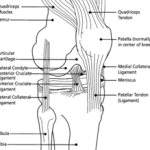

- Palpation: Tenderness of medial structures is evident. Palpable defects in the VMO, adductor mechanism, medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL), or a grossly dislocatable patella will suggest the need for surgery (Stefancin and Parker, 2007).

- Patellar Mobility and Apprehension Testing: often show excessive motion or positive apprehension

- Ligament Testing: required to exclude any concomitant ligament injuries

- Assessment of Generalised Ligament Laxity should also be performed, as a positive result indicates a poorer prognosis.

IMAGING

Imaging is an important component of treatment decision making following primary patellar dislocation.

X-RAY: should be performed in all primary patellar dislocations, and the series should include:

- AP extended WB view

- 45° flexion Merchant view (to identify osteonchondral fracture of medial patella)

- 45° flexion WB view

- 30° lateral view

CT: More sensitive to the presence of osteochondral fractures.

MRI: Is required when a haemarthrosis is present (even when radiographs are normal), as MRI are more accurate in the assessment of osteochondral lesions. MRI is also important to identify other pathology in the soft tissues, and will assess:

- Chondral surfaces

- Medial patellofemoral ligament

- Medial patellomeniscal ligament

- Medial retinaculum

- Medial patellotibial ligament

- VMO

NB: MRI is reliable for assessing for osteochondral lesions following primary patellar dislocation, with NPV of 92 – 98% and PPV of 55 – 100% dependent on injury grade (von Engelhard et al., 2010).

A CASE FOR PRIMARY SURGERY

The authors of the systematic review, Stefancin and Parker (2007), suggest that surgery is indicated in the following cases:

- Significant chondral injury

- Osteochondral fractures

- Large medial patellar stabilizer defects (i.e. MPFL, medial retinaculum, VMO)

- Subsequent dislocation

- Failure to improve with conservative management

CONSERVATIVE MANAGEMENT

The physiotherapy management of patellar dislocation should include the following:

A period immobilisation/bracing in extension (at least 3 weeks). This follows the results of Maenpaa and Lehto (1997) who found a 3-fold higher risk of redislocation in those treated with immediate mobilization, rather than a period of immobilisation.

This should be followed by functional rehabilitation, with the aims of:

- Quadriceps strengthening

- VMO Biofeedback – aimed at reducing inhibition

- Restoration of ROM

- Stretching of lateral structure tightness

- Mobilisation for cartilage nutrition

The outcomes of conservative management are quite favourable. The systematic review (Stefancin and Parker, 2007) showed an excellent to good results in 76% of patients, with an average re-dislocation rate of about 48%.

ASPIRATION

In patients who present with significant effusion, aspiration may aid both therapy and diagnosis (Stefancin and Parker, 2007). This is because:

- It can decrease pain and local anaesthetic injection can improve both clinical and radiographic assessment

- It will achieve joint depression.

- Larger haemarthrosis volume will be related to a larger injury to the medial patellar stabilizers and/or an osteochondral injury

- Analysis of the aspirate may identify the presence of fatty globules, which is indicative of an osteochondral fracture.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

As stated above, there are a number of cases in which surgical management is indicated. If the osteochondral fracture is greater than 10% of the patella articular surface, or if it is a part of the weight-bearing portion of the lateral femoral condyle, open repair is indicated (given that the fragment is amendable to fixation). Any large defects in the medial patellar stabilisers should under repair/reconstruction. A lateral release can also be performed to release tight lateral structures.

The results of surgical management are positive. Subjectively there has been excellent to good results in 69% of patients, with a lower re-dislocation rate of 12%.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

- Subjective and physical examination can be used to guide treatment and indicate prognosis

- It is essential to exclude concomitant injuries

- X-Ray series is essential in primary patellar dislocation; MRI is utilised as required.

- Physiotherapy (functional) rehabilitation must follow a period of immobilisation

- Quadriceps rehabilitation is the mainstay of rehab (but certainly not the only thing)!

- Primary surgical management is only indicated in certain discussed cases

What are your experiences with patellar dislocation rehabilitation – be sure to let me know in the comments or catch me on Facebook or Twitter

If you require any sports physiotherapy products be sure check out PhysioSupplies (AUS) or MedEx Supply (Worldwide)

REFERENCES

Aglietti P, Buzzi R, Insall J. Disorders of the patellofemoral joint. In: Insall J, Scott W, eds. Surgery of the Knee, 3rd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2001:913–1042.

Engelhardt LV, Raddatz M, Bouillon B, et al. How reliable is MRI in diagnosing cartilaginous lesions in patients with first and recurrent lateral patellar dislocations? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:149.

Harilainen A, Myllynen P, Antilla H, Seitsalo S. The significance of arthroscopy and examination under anesthesia in the diagnosis of fresh injury haemarthrosis of the knee joint. Injury. 1988;19:21–24.

Maenpaa H, Lehto MU. Patellar dislocation: the long-term results of nonoperative management in 100 patients. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:213-217

Jain NP, Khan N, Fithian DC. A Treatment Algorithm for Primary Patellar Dislocations. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2011 3: 170

Stanitski CL, Paletta GA Jr. Articular cartilage injury with acute patellar dislocation in adolescents: arthroscopic and radiographic correlation. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:52–55.

Stefancin JJ, Parker RD. First-time traumatic patellar dislocation: a systematic review.Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:93-101.

von Engelhardt LV, Raddatz M, Bouillon B, Spahn G, Dàvid A, Haage P, Lichting TK. How reliable is MRI in diagnosing cartilaginous lesions in patients with first and recurrent lateral patellar dislocations? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010 Jul 5;11:149.

Related Posts

Trackbacks

[…] Posted on 19. Apr, 2011 by The Sports Physiotherapist […]