Lateral elbow pain is a common complaint in many sports physiotherapy and physical therapy practices around the world. It is likely that this will surprise no-one. Lateral epicondylalgia, the most common cause of lateral elbow pain, has an annual prevalence of 1% to 2% in the general public (Shiri et al., 2006). Such a complaint is even more common in many groups of athletes (Hume et al., 2006; Mackay et al., 2003).

However, this is not an article about tennis elbow. It is about radial tunnel syndrome, a condition which has been suggested to be the main aetiopathogenetic (what a word) element in 4% of lateral epicondylalgia cases (Jalovaara & Lindholm, 1989). Interestingly, it causes headaches for the therapist in 100% of cases. This is because whilst radial tunnel syndrome is rare, it is challenging to differentially diagnose and can be a monster to manage. If you have a recalcitrant case of tennis elbow then this post will interest you! This article discusses the best available evidence for assessment and management of this condition.

What Is Radial Tunnel Syndrome?

Put simply, radial tunnel syndrome is a compressive neuropathy of the radial nerve in the upper limb. It is suggested that the radial nerve becomes irritated secondary to excessive friction or compression by the musculature in the forearm, normally between supinator and the radial head (Lutz, 1991). We know that compressive neuropathies of the upper limb are common (think: ulnar and median nerves.) However, radial nerve involvement is much less common. Radial tunnel syndrome is suggested to represent just 1-2% of upper limb nerve entrapments (Stanley, 2006).

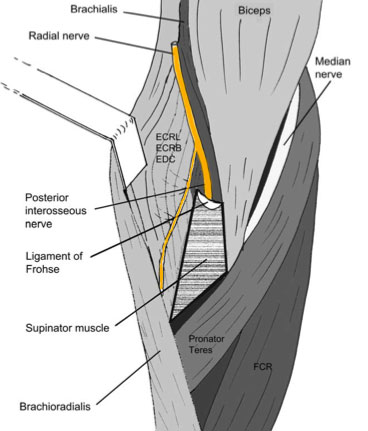

Unfortunately, you cannot have a thorough understanding of radial tunnel syndrome without an awareness of the complex anatomy of the area.

Pathoanatomy

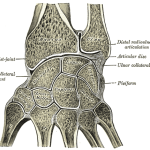

As you will recall from the cadaver labs; proximal to the supinator arch the radial nerve divides into 2 branches (Rosenbaum, 1999):

- Superficial Branch: Sensory superficial radial nerve

- Deep Motor Branch: Posterior interosseous nerve

The Radial Tunnel

This is a space created by the humeroradial joint and the proximal edge of the supinator muscle (Rosenbaum, 1999). Both the sensory superficial radial nerve and the posterior interosseous nerve travel through the radial tunnel, which is approximately 5cm in length. Numerous studies have shown that the supinator and extensor carpi radialis brevis are the most frequently implicated muscles and areas where fascial bands adhere or impinge upon the radial nerve (Huisstede et al., 2008).

Somewhat confusingly, in this proximal region of the forearm, the radial nerve is associated with two different syndromes:

- Radial tunnel syndrome (RTS)

- Posterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome (PINS) (Barnum et al., 1996; Plate and Green, 2000).

Whilst these 2 conditions are frequently not delineated in the literature, we will have a quick discussion about the differences in the 2 conditions.

RTS vs PINS

Where to begin. There is confusion because there is considerable overlap between the 2 conditions, and there are common clinical findings which include:

- Pain in the forearm

- Extensor weakness (sometimes secondary to pain)

However, it is suggested that PINS:

- Is caused by continuous or intermittent compression of the PIN in the radial tunnel (Konjengbam & Elangbam, 2004).

- Affects the motor portion of the nerve, and therefore patients present with loss of motor function or even complete palsy of one or more muscles innervated by the PIN

- Weakness and dysfunction is the primary symptom, not pain.

Whereas RTS:

- Affects only the sensory portion of the nerve; any weakness is secondary to pain (Barnum et al., 1996).

- May be caused by intermittent and dynamic compression of the nerve in the proximal part of the forearm associated with repeated pronation and supination (Portilla Molina et al., 1998)

- May also be caused by a lesion in the supinator muscle or in the septum between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum muscle (Verhaar and Spaans, 1991)

Risk Factors for Injury

Whilst there is some controversy, most of the literature suggests that radial tunnel syndrome is a consequence of repeated episodes of microtrauma, an overuse injury. In their study, Roquelaure et al. (2000) found occupational risk factors for the development of RTS included:

- Exertions of greater than 1 kg of force more than 10 times per hour

- Static pinching or squeezing of objects or tools

- Working with the elbow extended

- Maintained positioning of the forearm in pronation or supination

As you can see, such risk factors add weight to the belief that this syndrome develops secondary to overuse.

Subjective Assessment

The work of Stanley (2006) and Cleary (2006) outline the management of radial tunnel syndrome from a surgeon’s and clinician’s perspective respectively. They suggest that those with radial tunnel syndrome are likely to report:

- Pain: Over the radial proximal forearm. Unfortunately, pain at the lateral epicondyle is common making it difficult to differentiate from lateral epicondylalgia.

- Motor: Little or no motor weakness

- Aggravating Activties: Use of the upper extremity aggravates the pain.

- 24/24: Nocturnal symptoms, which awaken the patient, are often present. .

Objective Assessment

Again, the brilliant work by Stanley(2006) and Cleary (2006) outlines the objective examination of a patient with radial tunnel syndrome:

- Palpation: Pressure over the supinator on the lateral aspect of the elbow with the hand in full supination is painful. Forearm pronation may then relieve the pain (because the radial nerve is moved away from the pressure). The research Loh et al. (2004) discusses a more thorough examination technique termed the “Rule of Nine”. You can check out the full article here.

- Resisted Extension: as mentioned previously, may be weakened and painful

- Resisted Supination: contraction of supinator may cause compression of the nerve and pain (as opposed to tennis elbow)

- Neural Examination: should be performed. Frequently, radial nerve tension tests will be positive

- Posture: a full postural examination should be undertaken, it is essential that you do not just think distally. Often contributing pathology can occur proximally (discussed more below).

Imaging and Other Studies

Unfortunately, imaging and further studies are not very helpful in the diagnosis of radial tunnel syndrome:

- X-Ray: only useful to exclude potential competing hypotheses (degenerative elbow changes)

- MRI: often not able to determine the level to which the nerve is being irritated or compressed. Again, may be beneficial in excluding competing hypotheses.

- Nerve Conduction Studies: which are normally very helpful in identifying problems with median or ulnar nerves, are much less reliable, and there is considerable literature on the lack of reliability of nerve conduction studies on the radial nerve.

- Local Injection: short-acting local anesthetic is curative in patients who have a radial tunnel syndrome for a short period (Stanley, 2006).

Differential Diagnoses

As you have thought to yourself whilst reading this, there are many potential differential diagnoses to this condition. The research of Huisstede et al. (2008), Cleary (2006) and Stanley (2006) all suggest that potential differential diagnoses include:

- The Big One: lateral epicondylalgia

- PINS; as previously discussed

- Osteoarthritis or synovitis of the radial-capitellar joint

- A muscle tear of the extensor carpi radialis brevis or supinator

- Posterior plica impingement

- C6, C7, and C8 nerve root impingement

- Brachial plexux neuritis

- Double crush phenomenon: when both brachial plexus neuritis/thoracic outlet syndrome and radial tunnel/supinator syndrome may coexist.

Of course, this list is not exhaustive. There are many other potential causes of lateral elbow pain – any come to mind? – let me know in the comments below.

Conservative Physiotherapy Management of Radial Tunnel Syndrome

So by now we know what radial tunnel syndrome is and how to diagnose it (hopefully), but we want to know the important stuff: how do we fix it?! Well, unfortunately there is a dearth of research regarding the best way to manage this condition. In their systematic review, Huisstede et al. (2008) found no high quality articles discussing conservative management of radial tunnel syndrome.

However, Sarhadi et al (1998) had patients first undergo conservative treatment by means either corticosteroid injection, in 25 cases, or physiotherapy, in 1 case. The study reported that 16 patients (64%) were treated successfully by a conservative intervention. It is worth noting that this study was excluded from the systematic review discussed above secondary to low methodological quality.

Despite this Cleary et al. (2006) has proposed some treatment interventions for radial tunnel syndrome based not on research, but our current understanding of anatomy and aetiopathogenesis (I just wanted to sneak that in again!). We can also draw some insight into appropriate management from the work of Novak (2004), which discusses a treatment framework for upper-extremity work related disorders. Potentially beneficial interventions include:

Nerve Gliding Exercises

Which have been advocated to disperse intraneural edema, increase blood flow, optimize axonal transport, and lengthen nerve adhesions (Cleary, 2006).

Stretching Exercises

Novak (2004) suggests that tightnesses in the following muscles can contribute to upper extremity disorders such as radial tunnel syndrome:

- Supinator

- Extensor carpi radialis brevis

- Scapular muscles

- Cervical muscles

It is suggested that these tightnesses develop secondary to poor posture and may even impinge upon the nerve proximally. Therefore, stretching these areas may reduce impingement on the nerve.

Manual Therapies

Whilst not expressly discussed in the research, potentially beneficial manual therapies include:

- Soft tissue techniques to address myofascial limitations

- Spinal manual therapy for improved neural mobility and posture

- Any number of peripheral manual therapies to improve identified limitations in range or function

I hear you ask “what techniques do I use?”. It’s not too hard to use your imagination, but if you want some inspiration I recommend checking out the brilliant work of Erson Religioso.

Ergonomic Interventions

As previously discussed, Roquelaure et al. (2000) found occupational risk factors that contribute to radial tunnel syndrome. Thus, alteration or elimination of these aspects of work may be helpful in the treatment of RTS. This of course may include:

- Load management

- Postural awareness or changes

- Workstation alterations

Functional Strengthening

Cleary (2006) has suggested the importance of functional strengthening exercises, initially focussing on proximal stabilisation (think core and scapular stability). There is also a role for strengthening exercises to maintain improvement of soft tissue and spinal mobility as discussed by Novak (2004). For a range of scapular stability exercises, check out our post on treatment of scapular dyskinesis. If you are interested in learning more about strength and mobility work for posture, I recommend checking out the Postural Restoration Institute.

Surgical Management of Radial Tunnel Syndrome

Despite a lack of randomised controlled trials, there is consistent evidence from available case series that surgical decompression of radial tunnel syndrome yields improvement of symptoms in some percentage of patients. The systematic review by Huisstede et al. (2008) found the following results:

- Effectiveness of the surgical treatment ranged from 67% to 92%

- Patients’ satisfaction ranged from 40% to 83%.

Fortunately, this means that for those who do not respond to conservative management, surgical decompression may be a viable option.

Limitations of Evidence

Wow, there are many limitations to the current research. As previously suggested, there is a dearth of high quality research on evidence based assessment and management of radial tunnel syndrome. At last search, no randomised controlled trials existed. The best available studies are case series’, or systematic reviews of the same. Therefore, the research discussed above often includes methodological flaws…but let’s face it, it’s the best we’ve got!

A major limitation of the current search worth mentioning is that we are unaware of the natural history of radial tunnel syndrome. The included studies lack a control or placebo group. Therefore, the role of both conservative management and surgery is unknown.

Clinical Implications and Take Home Messages

The take home messages regarding radial tunnel syndrome include:

- There is a lack of high quality articles investigating radial tunnel syndrome

- The condition is rare, but should be considered in cases of recalcitrant tennis elbow

- Best available evidence shows some support and success with initial conservative management

- Surgical decompression shows favourable results in those who have failed conservative management

- Did I mention there is limited evidence available?

What Are Your Thoughts On This Research?

What are your experiences in the management of radial tunnel syndrome? I would love to know so be sure to let me know in the comments or you could:

References

Barnum M, Mastey RD, Weiss AP, Akelman E. Radial tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin 1996;12:679–689.

Jalovaara P, Lindholm RV. Decompression of the posterior interosseous nerve for tennis elbow. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1989;108:243–245.

Konjengbam M, Elangbam J. Radial nerve in the radial tunnel: anatomic sites of entrapment neuropathy. Clin Anat 2004;17:21–25.

Loh YC, Lam WL, Stanley JK, Soames RW. A new clinical test for radial tunnel syndrome—the Rule-of-Nine test: A cadaveric study. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery 2004;12(1):83–86

Lutz FR. Radial tunnel syndrome: An etiology of chronic lateral elbow pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1991;14(1):14-17

Novak CB. Upper extremity work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a treatment perspective. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:628–37.

Plate AM, Green SM. Compressive radial neuropathies. Instr Course Lect 2000;49:295–304.

Portilla Molina AE, Bour C, Oberlin C, Nzeusseu A, Vanwijck R. The posterior interosseous nerve and the radial tunnel syndrome: an anatomical study. Int Orthop 1998;22: 102–106.

Roquelaure Y, Raimbeau G, Dano C, et al. Occupational risk factors for radial tunnel syndrome in industrial workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26:507–13.

Rosenbaum R. Disputed radial tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve 1999;22:960–967.

Sarhadi NS, Korday SN, Bainbridge LC. Radial tunnel syndrome: diagnosis and management. J Hand Surg 1998; 23B:617– 619.

Shiri R, Viikari-Juntura E, Varonen H, Heliovaara M. Prevalence and determinants of lateral and medial epicondylitis: a population study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(11):1065-1074.

Stanley J. Radial tunnel syndrome: a surgeon’s perspective. J Hand Ther. 2006;19:180–5.

Verhaar J, Spaans F. Radial tunnel syndrome. An investigation of compression neuropathy as a possible cause. J Bone Joint Surg 1991;73A:539–544.

Image Credit: Akinori Li

Related Posts

In the past this site has featured some lighter, colloquial blog posts. These articles discuss issues related to the greater physiotherapy community. Thus, I present a few mantras I have heard, adapted or made up for the physios to live by in the coming year.

Radial tunnel syndrome is rare, it is challenging to differentially diagnose and can be a monster to manage. If you have a recalcitrant case of tennis elbow then this post will interest you! This article discusses the best available evidence for assessment and management of radial tunnel syndrome.