THE IMPACT OF PATIENT BELIEFS ON CLINICAL PRACTICE

In the retail and customer service world, we are told, the customer is always right. Whilst you may think that this has no relevance to the world of sports physiotherapy, where the athletes or patient are frequently wrong, it is surprising how frequently the athletes beliefs can affect your (yes, you!) clinical reasoning or practice.

Clinical Example 1. Consider the following clinical presentations: Two identical female twins (X and Y), both 24 year old elite tennis players present with painful dominant right shoulders. On clinical examination you find both have a glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) secondary to posterior capsule tightness. Accordingly you decide to perform a posterior capsule release, whilst explaining this to the athletes they say this:

X: “Yes, I feel like it needs a hard aggressive massage!”

Y: “I don’t think hard massage will work, soft is better in my opinion.”

What pressure do you use for the massages? Do both receive the same releases, or do you vary the pressure between them secondary to their preconceived notions?

Now, I would say that it is likely my pressure would vary between the two (but, of course, there would be some significant education involved). However, does this mean that one athlete will receive a more effective treatment than the other? Possibly…but not necessarily.

Thus, how much should patient beliefs affect our clinical practice? Good question, hey.

EVIDENCE BASED PRACTICE

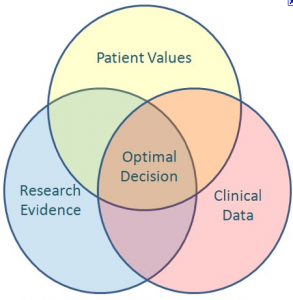

As I’m sure you would all know David Sackett is a renegade, or more appropriately pioneer, of evidence based practice. He has written that ‘the practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available clinical evidence from systematic research’ (Sackett, 1996). Interestingly, the more recent definitions, of which many of us are likely accustomed to, have included the beliefs and values in the EBP model (see image below).

This means that the thoughts of the patients are an important component of EBP. So where do we draw the line?

Clinical Example 2: An elite rower presents with a unilateral headache that is preceded by neck pain. You make a clinical diagnosis of cervicogenic headache, and develop a treatment protocol including manipulative therapy and deep cervical neck flexor control exercises. The athlete then says to you “I want ultrasound, it will help because it helped when I tore my hip flexor.”

What do you do?

I know different therapists who would take both sides on this subject. One, I know (let’s call him A), would stand with his hands on his hips (minus the soap box) and say “There is no good scientific evidence to support…bla bla bla”. The other (B) would just go “Yeah no worries, we’ll give it a go.”

Which is right? Well I think all will agree that neither are ideal situations, and the appropriate probably lies somewhere in the middle. Your stance, however, is exactly that, yours. However, you should be fully aware of the following important issues when making treatment decisions that are impacted by patients beliefs/values (correct or otherwise):

- Professional Integrity: Physiotherapists are not technicians (any more), nor are we fast food workers (now does the article picture make sense?). Patients should not come to us and ‘order’ their treatments, and anytime a physiotherapist allows this to occur it affects their integrity and the integrity of the profession. Imagine being physiotherapy B in the above example, and in the next aisle at the shopping centre you overhear your patient saying “I just tell my physio what to do and he does it.”.

- Patient Rapport: outright disagreement or belittling of patients will significantly affect your rapport with the patient. Consider Physio A above, how do you think the patient felt after the lecture… and I bet it wasn’t ‘My physio is so smart’.

- Informed Patient Decision Making: If you are going to use a treatment that does not have sound support in either scientific evidence or clinical experience then the patient should be fully informed, and you need to gain informed consent. In Clinical Example 2 it may be as simple as explaining that whilst there is some potential support for ultrasound in increasing collagen synthesis (this is not to open the flood gates) in a muscle tear it is unlikely to influence cervicogenic headaches.

- Duty of Care/Do No Harm: I don’t even need to elaborate, do no harm!

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

I doubt that I will get anyone argue that it is essential that the athlete/patient be an active participant in any intervention. However, clearly the extent to which their values or expectations should guide your interventions and clinical practice is a real grey area. I will be the first to admit I do not have all the answers, but if you do please let me know: in the comments or on Facebook or Twitter

If you require any sports physiotherapy products be sure check out PhysioSupplies (AUS) or MedEx Supply (Worldwide)

REFERENCES

Sackett, D. Evidence based medicine:what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996;312(13):71-72.

Related Posts

Comments

Trackbacks

-

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by The Sports PT. The Sports PT said: The patient is always right, unless they’re not! http://bit.ly/igq1YX […]

cool