Introduction

As most sports physiotherapists would know, injuries of the groin are very common. This is particularly true in sports that require lateral movements and kicking; think football, rugby and AFL (Waldén et al., 2005; O’Connor, 2004; Orchard and Seward, 2002). In fact in some sports the incidence of groin pain is as high as 13% (Ekstrand and Ringbord, 2001). This means that we are regularly assessing groin pathologies, and should be aware of the most effective and reliable techniques to assess deficits in adductor function. This article will discuss new research on the Adductor Squeeze Test that can inform and improve your clinical practice.

Why Do We Care About Adductor Strength?

It may be obvious to many sports physiotherapists, but we care about adductor strength for a number of reasons. Adductor strength is an important objective outcome for both rehabilitation and prevention of groin injuries, as it has been shown:

- Decreased hip adductor strength precedes groin injury in some populations (Crow et al., 2010)

- Weak adductor muscles are an intrinsic risk factor for groin injuries (Engebretsen et al., 2010)

- Hip adductor strength is reduced by groin injury (Crow et al., 2010)

- Adductor strength can be utilised as an outcome to show improvements and may be helpful to gauge return to play readiness

Thus, it is obvious that there are many reasons why sports physiotherapists are interested in an athlete’s groin strength, and the above list is in no way exhaustive. So, how is the best way to measure the adductor strength?

What Is The Best Way To Perform The Adductor Squeeze Test?

The Adductor Squeeze Test is widely used in clinical practice as a technique to evaluate the strength of the adductor muscles, through the use of a forceful bilateral isometric contraction of the adductor muscles onto the pressure cuff of a sphygmomanometer that is pre-inflated to 10mmHg (Delahunt et al., 2011). However, until recently we have had only anecdotal evidence to identify the ideal position of hip flexion for optimal force production and adductor muscle activity.

Enter Delahunt and colleagues (2011), who evaluated the Adductor Squeeze Test in 18 asymptomatic male Gaelic football players. The authors compared 3 test positions (0, 45 and 90 degrees of hip flexion) for sEMG activity of the adductor muscles and force production. Interestingly, they found that 45 degrees of hip flexion elicited the greatest EMG activity of the adductor mass and this correlated to the greatest force production (mean 236.76 ± 47.29 mmHg). This was followed by 0 degrees (202.50 ± 57.28 mmHg) and finally 90 degrees (186.11 ± 44.01 mmHg).

This suggests 45 degrees of hip flexion as the optimal Adductor Squeeze Test position. Importantly, it also serves as a preliminary profile of ‘normal’ results in this population. Unfortunately, this sEMG study does not allow for differentiation between the individual muscles of the adductor mass in the different testing positions. This, of course, would be useful in improving diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination of groin pain. This research should also be repeated in various injury groups, e.g. acute vs chronic, to establish generalisability to other populations. Clearly, further research in this field is warranted and I for one cannot wait…

Clinical Implications

- Adductor strength is a clinical indicator used in both injury prevention and rehabilitation, and should be monitored

- 45 degrees of hip flexion provides optimal force and adductor muscle activity during the Adductor Squeeze Test in this population

What are your thoughts on this research and the use of the Adductor Squeeze Test in clinical practice? Be sure to let me know in the comments or you could:

Promote Your Clinic: Are you a physiotherapist or physical therapist looking to promote your own clinic? Check this out.

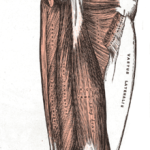

Photo Credit: BabaSteve

References

Crow JF, Pearce AJ, Veale JP, Vander Westhuizen D, Coburn PT, Pizzari T. Hip adductor muscle strength is reduced preceding and during the onset of groin pain in elite junior Australian football players. Journal of Sciences and Medicine in Sport 2010;13(2):202-4.

Delahunt E, Kennelly C, McEntee BL, Coughlan GF, Green BS. The thigh adductor squeeze test: 45 of hip flexion as the optimal test position for eliciting adductor muscle activity and maximum pressure values. Manual Therapy 2011;16:476-480.

Ekstrand J, Ringborg S. Surgery versus conservative treatment in soccer players with chronic groin pain: a prospective randomised study in soccer players. Eur J Sports Traumatol 2001;23:141–5.

Engebretsen AH, Myklebust G, Holme I, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Intrinsic risk factors for groin injuries among male soccer players: a prospective cohort study. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2010;38(10):2051-7.

O’Connor D. Groin injuries in professional rugby league players: a prospective study. Journal of Sports Sciences 2004;22(7):629e36.

Orchard J, Seward H. Epidemiology of injuries in the Australian football league, seasons 1997-2000. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2002;36(1):39-44.

Waldén M, Hägglund M, Ekstrand J. UEFA champions league study: a prospective study of injuries in professional football during the 2001-2002 season. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2005;39(8):542-6.

Related Posts

Comments

Trackbacks

-

[…] how we assess these types of injuries in our athlete’s. The main topic of the article was the adductor squeeze test and why it is important to have good adductor […]

just thinking biomechannically do you think its fair assumption that in positions of 90 degrees hip flexion we would see a greater recruitment of horizontally orientated fibres of pectineus?

Interesting point Andrew, do you think given pectineus is primarily a hip flexor even the more horizontal fibres may not be effective adductors in this position of hip flexion? I’m really not sure! I do think in this position (90 degrees) we will see greater levels of abdominal activity (i.e. rectus abdominis) and thus those with conditions such as pubic symphisitis would likely find this position very provocative. I am also interested in the different length-tension relationships of the positions, for example would you agree gracilis, which crosses the knee, may have a greater mechanical advantage (and thus be more active) with the hip and knee in 0 degrees? I am very interested in these concepts, but of course these are all assumptions, until we get more research… Thanks for your input!

The result of your test can also be very much effected by the pelvic position, you can get very different pressure readings at the same hip angle by asking the athlete to move through different pelvic tilt angles. Not sure why as different athletes respond differently to these positions.

I recently listened to the podcast ‘preventing groin injuries” with Jeff Boyle. He states that adductor strength is not a ‘red flag’ for identifying athletes at risk of developing groin pain, and that adductor strength is normal proceeding and ‘well into’ the player reporting pain.

This seems to be contrast to the research presented in the above article?

I currently work with professional football (soccer) players and personally love the work form Crow et. al. Testing the adductor strength of players once per week has enabled us to improve our identification of ‘at risk’ athletes and further reduce our incidence of groin related injuries (this one intervention is of course just one part of a larger injury prevention program)

Would love to know other peoples thoughts on this issue.

Thanks for your input Robert!

Its great to hear about those working with different elite populations i.e. soccer vs AFL. I too would love to hear from the greater physio population.