Introduction

The majority of the sports physiotherapists reading this will know the incredible frequency with which we treat athletes with patellofemoral pain syndrome. There is a good reason for this, it is the most commonly reported injury sustained by runners (Taunton et al., 2002). Whilst the mainstays of treatment have previously focussed solely on the patellofemoral joint, we are seeing more research identifying the importance of the assessing the other components of the kinetic chain. This has been the topic of previous articles on this site, here we discuss the impact of proximal hip strengthening for patellofemoral pain syndrome. This article will discuss new research on the impact of real time gait retraining for patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Please note if you would rather read the full article it is available for free from the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

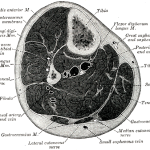

Hip Kinematics in Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

As suggested above, there is an ever-growing body of evidence to support the existence of altered hip kinematics in athletes with patellofemoral pain syndrome. This includes:

- Increased hip internal rotation (HIR) during WB activities (Powers et al, 2003)

- Increased hip adduction (HADD) causing a dynamic valgus alignment (Souza et al, 2009)

- Weakness of the hip abductors and external rotators (Bolgla et al, 2003)

These dysfunctions may contribute to patellofemoral pain syndrome as increased lateral patellar contact pressure has been demonstrated in those with:

- Increased Q angle and associated with HADD (Huberti et al., 1984)

- Increased femoral internal rotation (Li et al., 2004)

The Effect of Real Time Gait Retraining

Noehren and colleagues (2011) took 10 runners (who were all female) with a diagnosis of patellofemoral pain and identified altered hip kinematics i.e. excessive dynamic hip adduction and gave them 8 sessions of real time gait retraining over a 2 week period. They used the high tech stuff; 3D biomechanical analysis and modeling software for real time athlete feedback. Essentially, they gave feedback to the athlete to make an effort to contract the gluteals in an attempt to run with the knee and pelvis in good alignment.

After the 2 week training period and at 1 month follow up (when the athletes had returned to normal running activities) there were some incredible results. Most notably they showed improvements in:

- HADD during running of 5.0° (23%)

- Contralateral pelvic drop during running

- Average pain of 86% reduction during running

- Function, 11 points on the Lower Extremity Functional Index

- Kinematics on a “non-trained” skill: Single Leg Squat

- Retained improvements at 1 month follow up

Limitations of this Research

There are a few obvious limitations to this research, of which the authors are aware. The first and most obvious is the expensive equipment required to undertake the same intervention as described in the study. This questions the generalisability to widespread clinical uses and warrants investigations into the success of other forms of “low-tech” visual biofeedback. We too have the common offenders of small sample size, no blinding, placebo or control, and short-term follow up. Additionally, the sample included only women, as they were found to have the kinematic deviations required for inclusion. This may suggest this intervention is best suited to female athletes and supports previous research on these changes being more common in females (Powers et al., 2003, Souze et al., 2009).

Clinical Implications of This Research

This is preliminary research and as such does not allow us to make clear clinical judgements. However, it does add to the growing body of evidence that shows correcting kinematic deviations or abnormal dynamic pelvic alignment provides favourable results in those with patellofemoral pain syndrome, particularly females. Therefore, in patellofemoral pain syndrome patients with poor running mechanics, gait retraining may be considered as a component of their rehabilitation program.

What are your thoughts on this new research, will it change the way you look at management of patellofemoral pain syndrome athletes? Be sure to let me know in the comments or catch me on Facebook or Twitter

If you require any sports physiotherapy products be sure check out PhysioSupplies (AUS) or MedEx Supply (Worldwide)

References

Bolgla LA, Malone TR, Umberger BR, Uhl TL. Hip strength and hip and knee kinematics during stair descent in females with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:12-18.

Huberti HH, Hayes WC. Patellofemoral contact pressures. The influence of q-angle and tendofemoral contact. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984;66:715 – 24 .

Li G, DeFrate L, Zayontz S, et al. The effect of tibiofemoral joint kinematics on patellofemoral contact pressures under simulated muscle loads . J Orthop Res 2004:22;801 – 6.

Noehren B, Scholz J, Davis I. The effect of real-time gait retraining on hip kinematics, pain and function in subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:691-696.

Powers CM, Ward SR, Fredericson M, Guillet M, Shellock FG. Patellofemoral kinematics during weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing knee extension in persons with lateral subluxation of the patella: a preliminary study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:677-685.

Souza RB, Powers CM. Differences in hip kinematics, muscle strength, and muscle activation between subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:12- 19

Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, et al. A retrospective case–control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med 2002;36:95 – 101.

Related Posts