Introduction to Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

To explain the importance of knowledge about these conditions I will frequently tell you how common these ligament injuries are. Well, it has been suggested that up to 37% of all patients with knee haemarthroses have an associated PCL injury (Wind et al., 2004). That is right, a whopping 37%! Furthermore, the incidence of injury is particularly high in sports that involve heavy contact. That means that sports physiotherapists that are involved in the management of athletes from contact sports need to be aware of the evidence based assessment and management of these ligament injuries.

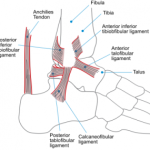

Anatomy of the Posterior Cruciate Ligament

The primary function of the PCL is to restrict posterior tibial translation. Additionally, it acts as a secondary restraint to tibial varus, valgus, and external rotation.The posterior cruciate ligament is thick and strong (31.2 sq/mm at its midsubstance). Interestingly, it is 1.5 times thicker than that the ACL. As you will know, the PCL is divided functionally into two bundles (Van Dommelen and Fowler, 1989)

- Anterolateral (AL) bundle: taut in flexion, lax in extension

- Posteromedial (PM) bundle: taut in extension, lax in flexion

As can be seen in the above image, there are also 2 menisco-femoral ligaments, which provide additional support to the posterior knee. These ligaments arise from the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus and insert on the the medial femoral condyle, and they are:

- Anterior ligament of Humphrey

- Posterior ligament of Wrisberg

Mechanism of Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

Posterior cruciate ligament injury in the athlete generally occurs by 1 of 3 mechanisms:

- A fall on the flexed knee with a plantar-flexed foot and hyper-flexion of the knee

- Hyper-extension

- Direct posterior tibial force on a slightly flexed knee

These 3 mechanisms will stress and potentially injure the posterior restraints of the knee.

Subjective Assessment

The athlete will who has suffered a posterior cruciate ligament injury will generally report:

- A mechanism that fits with the one of the above

- No significant “pop” or “tear” (in isolated PCL tears)

- Pain is generally felt in the posterior knee

Objective Assessment

- Gait: moderate limp

- ROM: generally lack 10° to 20° of flexion

- Special tests that will assist in the diagnosis of PCL injury are:

Posterior Sag Test

Sensitivity: 79%

Specificity: 100% (Malanga et al., 2003)

Posterior Drawer Test

Sensitivity: 51 – 90%

Specificity: 99% (Malanga et al., 2003)

Quadriceps Active Test

Sensitivity: 54-98%

Specificity: 97 – 98 % (Malanga et al., 2003)

As well as diagnosing the PCL rupture, it is essential to exclude concomitant injury to the:

- Posterolateral corner (Dial Test can be helpful)

- Posteromedial corner (Pivot Shift can be helpful)

- ACL Injuries (Lachman’s, Pivot Shift and Anterior Drawer)

- Collateral Ligament (Varus and Valgus stress testing)

NB: It is necessary to perform a neurovascular examination. This will include distal pulses (dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial) and motor/sensory (particularly in the peroneal nerve distribution).

Imaging Assessment

X-Ray: can be useful to diagnose:

- Arthritis (especially the flexion weight-bearing views)

- Avulsion fractures

- Lateral joint space widening

- Posterior sag may be evident on a lateral view

- Stress radiographs with an axial view have been shown to be accurate in demonstrating posterior instability (Guddu et al., 2000)

Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Is the gold-standard of imaging to diagnose PCL injury. The diagnostic accuracy in the range of 96% to 100% (Wind et al., 2004). MRI is necessary to determine:

- The location of the PCL injury

- Other ligament injury

- Meniscal injury

- Cartilage injury

Conservative Physiotherapy Management

Isolated injuries of the PCL can generally be managed non-operatively (Wind et al., 2004). In the majority of cases this will deliver good to great objective and subjective results for the athlete (Shino et al., 1995; Wind et al., 2004). Optimal management of grade III injuries is controversial as these injuries often have concomitant PMC or PLC injuries (Wind et al., 2004). Below is a rough outline of the phases and goals of management during conservative physiotherapy rehabilitation of posterior cruciate ligament injury:

Surgical Management

As stated above isolated injuries to the posterior cruciate ligament can usually be managed conservative with physiotherapy. The current surgical indications for PCL injuries include:

- Failure after a period of conservative management

- Combined ligamentous injuries involving the PCL

- Symptomatic grade III laxity

- Bony avulsion fractures

There are a number of surgical techniques available for posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The graft choices include:

- Autologous bone–patellar tendon–bone

- Autologous hamstring tendon

- Autologous quadriceps tendon

- Achilles tendon allografts

- Open vs. arthroscopic

- Single vs. double bundle grafts

- Tibial inlay vs. tibial tunnel technique

Unfortunately, there is no clear evidence for the use of any technique over another. Frequently it will come down to the preference of the surgeon. The lack of quality evidence is shown by the systematic Cochrane review which found NO articles that met its inclusion criteria (Peccin et al., 2005).

Return to play following posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is dependent upon the preference of the orthopaedic specialist, however, usually takes 6 – 12 months (Wind et al., 2004).

Take Home Messages

- There is a significant lack of quality research in this field

- Posterior cruciate ligament injury must be excluded in knees with a haemarthrosis

- Accurate diagnosis requires a combination of subjective, objective and imaging information

- Conservative management can provide good outcomes in isolated PCL injuries

- Surgical management is indicated in certain cases

What are your thoughts on the management of PCL injuries? Be sure to let me know in the comments or catch me on Facebook or Twitter

If you require any sports physiotherapy products be sure check out PhysioSupplies (AUS) or MedEx Supply (Worldwide)

Photo Credit: martha_chapa95

References

Malanga GA, Andrus S, Nadler SF, McLean J. Physical examination of the knee: a review of the original test description and scientific validity of common orthopedic tests. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:592-603.

Peccin MS, Almeida GJM, Amaro JT, Cohen M, Soares B, Atallah ÁN. Interventions for treating posterior cruci- ate ligament injuries of the knee in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2.

Puddu G, Gianni E, Chambat P, Paulis FD. The Axial View in Evaluating Tibial Translation in Cases of Insufficiency of the Posterior Cruciate Ligament. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery 2000;16(2):217-22

Richter M, Kiefer H, Hehl G, Kinzl L. Primary repair for posterior cruciate ligament injuries: an eight-year followup of fifty-three patients. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:298-305.

Shino K, Horibe S, Nakata K, Maeda A, Hamada M, Nahamura N. Conservative treatment of isolated injuries to the posterior cruciate ligament in athletes. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – British Volume 1995;77(6):895-900

Van Dommelen BA, Fowler PJ. Anatomy of the posterior cruciate ligament: a review. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:24-29.

Wind WM, Bergfeld JA, Parker RD. Evaluation and treatment of posterior cruciate ligament injuries : Revisited. Am J Sports Med 2004 32: 1765

Related Posts

Comments

Trackbacks

-

[…] Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: Evidence Based Diagnosis and … […]

Gday thanks heaps for the great articles and podcasts! Do you find surgeons reconstructing if there is posterolateral corner instability? Does MRI help with determining if the posterolateral corner has been injured? Cheers Mark