Have you ever heard of snapping scapula syndrome? If you answered no, I would not be too surprised. Whilst this condition is more common than you may think, it seems to be underappreciated within the world of physiotherapy. This is a disorder that ranges from inconvenience for some to truly disabling to others (Manske et al., 2004). Of even greater interest is that it is related to many sports including swimming, baseball pitching and weight-training. Thus, this article will discuss snapping scapula syndrome including what it is, why it occurs and what you need to do to fix it!

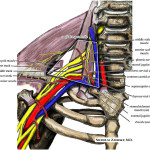

Anatomy of the Scapulothoracic Joint

Whilst I won’t labour the anatomy of the scapulothoracic joint (I’m sure that you all know it), it is worth noting the scapula relies primarily on the surrounding muscles for support and stability (Voight & Thomson, 2000). The joint itself can be divided into 3 layers, each consisting of musculature and bursae.

Superficial

- Muscles: trapezius and lat dorsi

- Bursa: inferior angle bursa (1.9 x 2.4cm) between the inferomedial angle of the scap and lat dorsi

Intermediate

- Muscles: rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, and levator scapulae

- Bursa: trapezial bursa (4.3 x 2.7cm) between the trapezius and spine of the scapula

Deep

- Muscles: serratus anterior and subscapularis

- Bursae:

- Scapulothoracic, or supraserratus, (9 x 7.4cm) between serratus anterior and the thoracic cage

- Subscapularis, or infraserratus, (5.3 x 5.3cm) between subscapularis and serratus anterior

Whilst any of the above bursa can become irritated, the bursae of the deep layer are most commonly implicated in snapping scapula syndrome.

Snapping Scapula Syndrome (Scapulathoracic Bursitis) Pathophysiology

Similar to other bursitis presentations, scapulothoracic bursitis may occur following episodes of micro-trauma or one episode of macro-trauma (Pearse et al., 2006; Richards & McKee, 1989). There are many potential causes, which include:

- Soft tissue abnormality: leading to increased curvature of the superomedial angle of the scapula (Milch & Buran, 1933)

- Luschka tubercle: a hook-shaped prominence at the superomedial angle of the scapula (6% of cases) (Edelson, 1996).

- Osteochondroma: the most prevalent benign tumor of the scapula (16% of cases) (Carlson et al., 1997)

- Skeletal abnormalities including exostoses or other osseous tumors

- Scapular dyskinesis or loss of dynamic control of scapular motion (Lehtinen et al., 2004). This may occur secondary to:

- Muscle overuse

- Muscle imbalances

- Nerve injury,

- Glenohumeral pathologies (Strizak & Cohen, 1982)

Subjective Assessment

Lazer et al (2009) and Manske et al (2004) suggest those with scapulothoracic bursitis may report:

- Mechanism: potentially insidious onset or traumatic

- Aggravators: use of arm, particularly overhead

- Pain: present around scapula (particularly medially). May also present with shoulder girdle and neck pain

- Mechanical: feeling of crepitus around scapula, described as a snapping, grinding, thumping, or popping sound (Manske et al., 2004)

Great vid to listen to a snapping scapula

Objective Assessment

Lazer et al (2009) and Manske et al (2004) suggest that those with scapulothoracic bursitis may display:

- Posture: increased thoracic kyphosis and cervical kyphosis

- Scapula Position: abducted and forward tipped scapulae. Check out our post on assessing scapula position

- AROM: shoulder motion is likely to be painful, and may be reduced

- Scapular Dyskinesis: scapulo-humeral rhythm should be fully examined. Check out our post on assessing scapular dyskinesis

- Crepitus: may be palpable. Is generally softer when associated with soft tissue lesion rather than skeletal lesion (Kuhn et al., 1998)

- Palpation: periscapular palpation may reproduce pain

Potential Differential Diagnoses

As with all diagnoses you should be aware of potential differential diagnoses. A few to be aware of include:

- Cervical radiculopathy

- Thoracic referred pain

- Glenohumeral pathology

- Thoracic outlet syndrome

- Neurological injuries

As per usual, this list is not exhaustive… but you should always be thinking of potential DDx.

Imaging Assessment

X-Ray

Standard radiographs may be used to assess skeletal abnormalities including:

- Osteochondromas

- Luschka tubercle

- Rib abnormalities

- Superomedial or inferomedial angle of the scapula abnormalities

The appropriate views for snapping scapula syndrome include:

- True anteroposterior

- Tangential transscapular (or Y)

- Axillary lateral view

Computerised Tomography (CT)

CT can also be used to assess the above skeletal abnormalities. Unfortunately, de Haart et al (1994) suggested that CT was not justified for patients with scapulothoracic bursitis as the results of the scan did not correlate well with a clinical assessment. However, CT is seen as an important adjunct to x-ray for surgical planning.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

As we all know, MRI is more useful in identifying soft tissue abnormalities. Accordingly, MRI can be used to assess fluid-filled or inflamed bursal tissue. It is also beneficial for differentiating pseudotumours, such as scapulothoracic bursitis vs. elastofibroma. MRI may also be beneficial in excluding competing hypotheses.

Ultrasound

The dynamic nature of ultrasound is what makes it beneficial. By allowing the dynamic identification of bursal tissue, ultrasound can assist with image-guided injections (discussed further below) (Saboeiro & Sofka, 2007).

Conservative Management of Snapping Shoulder Syndrome

It is important for physiotherapists and physical therapists to be aware that the vast majority of patients with scapulothoracic bursitis (or crepitus) can be successfully managed conservatively (Lazar et al., 2009). Surgical intervention is indicated only in patients with a clearly identifiable osseous or soft-tissue mass or who have failed conservative management. The cornerstones of therapy include:

- Physiotherapy

- Anti-inflammatory medications

- Corticosteroid injections (Millett et al., 2006)

Physiotherapy Rehabilitation of Scapulothoracic Bursitis

As previously indicated, conservative physiotherapy management has been effective in the majority of cases. Ciullo et al (1992) reported excellent results in 62/72 patients using a combination of electrophysical agents and strengthening of the scapular and rotator cuff musculature. Supporting this finding, Groh et al. (1996) found good or excellent results in 22/30 patients with peri-scapular strengthening.

Previous research has advocated a general 3 phase rehabilitation program (Kibler, 2001)

Phase 1: Pain Reduction

- Goals: reduce pain and inflammation, restore normal alignment

- Principles: pain-free ROM, gravity eliminated, closed kinetic chain exercises

- Examples: manual therapy (soft tissue and spinal), co-contractions, thoracic motion exercises, scapular retraction, sidelying flexion, stretches as appropriate

Phase 2: Recovery Phase

- Goals: strengthening through ROM to improve scapulo-humeral rhythm

- Principles: increased planes and ranges of motion, external load as required

- Examples: for some great exercise examples check out our post on treatment of scapular dyskinesis

Phase 3: Maintenance Phase

- Goals: maintain ROM, scapula control, increase complexity

- Principles: advanced open kinetic chain, plyometric exercises, combination exercises

- Examples: medicine ball tosses, walking lunges with shoulder press

As is frequently discussed on this site – this is a general guideline and by no means a recipe. The prescribed exercises and phases utilised are patient dependent.

Corticosteroid Injection

Hodler et al (2003) found benefit in 18/20 patients injected with corticosteroid for the treatment of scapulothoracic bursitis. This positive result has been supported by the work of others (Lazar et al., 2009).

Surgical Management of Snapping Scapula Syndrome

In those with an obvious osseous abnormality or in recalcitrant cases treated with physiotherapy, surgical management may be considered (Manske et al., 2004: Lazer et al., 2009). There are multiple surgical techniques that may be considered. Unfortunately, due to a lack of large scale high quality studies there is no clear benefit of any technique. Surgical techniques include:

Arthroscopic Treatment

There are many potential benefits of arthroscopic management including:

- Preserved muscle attachments

- Reduced postoperative immobilization

- Potential shortening of hospital stay and rehabilitation period (Harper et al., 1999)

Arthroscopic surgical techniques include:

- Bursectomy: debridement of thickened/fibrotic bursal tissue

- Partial Scapular Resection: used to treat any osseous impingement

Outcomes from this surgery are positive, with good to excellent results in the majority of patients (Lazar et al., 2009).

This vid shows the arthroscopic surgery

Open Treatment

Historically, open resection of the superomedial angle of the scapula has been the most common surgical technique (Manske et al., 2004). Similar to arthroscopic management, open surgical management has resulted in good-to-excellent outcomes in the majority of patients (Manske et al., 2004: Lazer et al., 2009).

However, unlike the more technically challenging arthroscopic technique, open treatment requires the detachment of muscles from the medial spine of the scapula (rhomboids, levator scapulae, trapezius). This allows the surgeon access to the area for bursectomy and potential scapular resection. As suggested previously, this means there is a period of immobilisation following surgery (up to 4 weeks). Post-operative rehabilitation then includes progressive range of motion with active ROM at 8 weeks and resistance/strengthening at 12 weeks (Manske et al. 2004).

Outcomes: Despite the surgical technique utilised most patients returned to work or their respective sports in about 3 to 4 months (Manske et al., 2004)

Clinical Implications and Take Home Messages

- Snapping scapula syndrome (scapulothoracic crepitus or bursitis) is likely underappreciated in the sports medicine world

- Diagnosis is generally made clinically

- In many cases imaging may be of little benefit/clinical utility

- Conservative management should be trialled originally, and is effective in the majority of cases

- Surgical management is indicated only in recalcitrant cases, and is also effective in the majority of cases

What Are Your Thoughts?

What are your experiences working with snapping scapula syndrome? I would love to know so be sure to let me know in the comments or you could:

Promote Your Clinic: Are you a physiotherapist or physical therapist looking to promote your own clinic? Check this out.

References

Carlson HL, Haig AJ, Stewart DC. Snapping scapula syndrome: three case reports and an analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:506-11.

Ciullo JV. Subscapular bursitis: treatment of ‘‘snapping scapula’’ or ‘‘wash-board syndrome’’. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:412-3.

de Haart M, van der Linden ES, de Vet HC, Arens H, Snoep G. The value of computed tomography in the diagnosis of grating scapula. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23:357-9.

Edelson JG. Variations in the anatomy of the scapula with reference to the snapping scapula. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:111-5.

Groh GI, Simoni M, Allen T, Dwyer T, Heckman MM, Rockwood CA Jr. Treatment of snapping scapula with a periscapular muscle strengthening program. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(2-Pt 2):S6.

Harper GD, McIlroy S, Bayley JI, Calvert PT. Arthroscopic partial resection of the scapula for snapping scapula: a new technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:53-7.

Hodler J, Gilula LA, Ditsios KT, Yamaguchi K. Fluoroscopically guided scapulothoracic injections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1232-4.

Kibler WB, Livingston B. Closed-chain rehabilitation for upper and lower extremities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9:412-21.

Kuhn JE, Plancher KD, Hawkins RJ. Symptomatic scapulothoracic crepitus and bursitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:267-73.

Lazar MA, Kwon YW, Rokito AS. Snapping scapula syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2251-2262

Lehtinen JT, Macy JC, Cassinelli E, Warner JJ. The painful scapulothoracic articulation: surgical management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;423:99-105.

Manske RC, Reiman MP, Stovak ML. Nonoperative and operative management of snapping scapula. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(6):1554-65.

Milch H, Burman MS. Snapping scapula and humerus varus. Report of six cases. Arch Surg. 1933;26:570-88.

Nicholson GP, Duckworth MA. Scapulothoracic bursectomy for snapping scapula syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:80-5.

Pavlik A, Ang K, Coghlan J, Bell S. Arthroscopic treatment of painful snapping of the scapula by using a new superior portal. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:608-12.

Pearse EO, Bruguera J, Massoud SN, Sforza G, Copeland SA, Levy O. Arthroscopic management of the painful snapping scapula. Arthroscopy. 2006; 22:755-61.

Richards RR, McKee MD. Treatment of painful scapulothoracic crepitus by resection of the superomedial angle of the scapula. A report of three cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;247:111-6.

Saboeiro GR, Sofka CM. Imaging-guided treatment of scapulothoracic bursitis. HSS J. 2007;3:213-5.

Strizak AM, Cowen MH. The snapping scapula syndrome. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:941-2.

Voight ML, Thompson BC. The role of the scapula in the rehabilitation of shoulder injuries. J Athl Train. 2000;35:364-372.

Photo Credit: Swamibu

Related Posts